- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Part sorting growing pains

The speed of fiber laser cutting has made it challenging for part sorting practices to keep up

- July 12, 2016

- News Release

- Fabricating

With the increased processing speeds in flat sheet laser cutting made possible by fiber laser technology, and advances in press brake efficiencies, part sorting has become perhaps the biggest bottleneck in part fabrication.

“Early laser cutting machines working in thin-gauge material may have cut 300 inches per minute, but with fiber lasers, today we’re running at 2,000 IPM,” pointed out Tobias Reuther, TRUMPF product manager, automation group.

Both manual and automated processes can simplify and speed up the sorting process, however. The challenge is finding the right approach for your shop.

Simplified Manual Processing

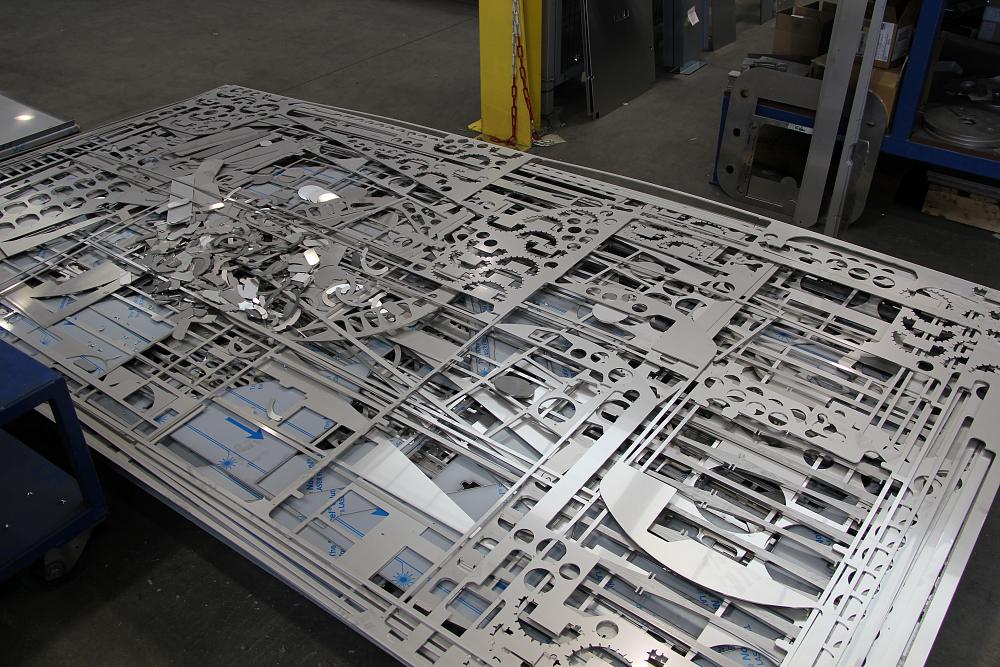

One of the most basic challenges of removing parts from a cutting table is the skeleton. Removing parts from a skeleton the size of the original metal sheet can be cumbersome because it’s necessary to reach across the table to lift parts out of it. Small parts often require microjoints to ensure that they don’t fall below the skeleton or between the slats. Reaching across a full skeleton to remove these parts is also awkward and is ergonomically less than ideal.

Frank Arteaga, Bystronic’s head of product marketing for the NAFTA region, recommends doing a stitch cut prior to processing the nest to make part removal easier.

“A stitch cut essentially partitions the sheet in 2- or 3-foot sections,” said Arteaga. “The stitch cuts are made before you cut any actual parts on the sheet. Then, as you cut the part, it breaks into those channels. Once you finish a whole row of parts, then that portion of the sheet will be dislodged from the main sheet. When it is all done, it becomes very manageable. Removing the parts becomes a one-man operation rather than a two-man operation, or a one-man operation without the use of a hoist to take out the skeleton.”

As LVD Strippit Laser Product Sales Manager Stefan Colle noted, being able to remove the skeleton in smaller pieces like this is also beneficial for scrap removal because those who process scrap prefer dealing with smaller sections.

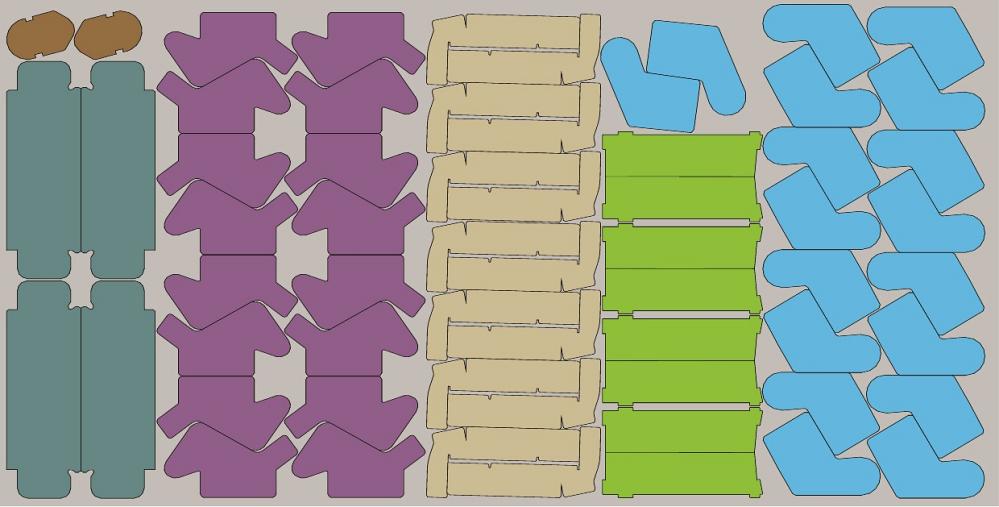

Sometimes simple guidance with a sheet can speed parting processes. With a screen in front of the cut sheet, it is simple for the operator to see which parts need to be picked up and sorted together. Pictured here is LVD Strippit’s TOUCH-i4 tablet. Among other functions, an operator can use the tablet to review what is on a pallet and which parts should be grouped together in the sorting process.

Sometimes simple guidance with a sheet can speed parting processes as well. Michael Beransky, executive general manager of Amada’s Automation Engineering division, noted that with his company’s nesting software, it is possible to colour-code parts on the nest so that, with a screen in front of the cut sheet, it is simple for the operator to see which parts need to be picked up and sorted together.

LVD Strippit offers guidance capabilities through its TOUCH-i4 tablet. This industrial-strength, Windows®-based tablet provides an overview of the entire fabrication workshop. It generates and presents live information needed to manage networked LVD Strippit laser, punching, and bending machines. With the tablet, an operator can review what is on a pallet and which parts should be grouped together in the sorting process.

“Using this you can pull up the nesting of the part and can see what has been cut on a sheet,” said Colle. “This is helpful also to determine whether all of the parts that were supposed to be cut are indeed accounted for.”

Nesting

Nesting itself can also play a role in simplifying the removal of the sheet skeleton and parts, while also speeding up the cutting process. At the most basic level, the grouping of similar or related parts on a section of sheet, of course, can help an operator remove and stack those parts together. Taking this a step further, by removing the need for a skeleton between those parts, you save materials and scrapping processes.

For instance, with its ByOptimizer nesting software, Bystronic makes what Arteaga called the “dynamic clustering” of parts possible.

“This enables you to make groupings of a similar part into a cluster that eliminates a lot of the waste you typically find in nesting standards,” Arteaga explained. “For instance, it may be that you cut all the holes in a cluster first, then cut some separation lines in the middle, followed by one peripheral cut around the edge of the parts.”

With clustering, many parts might share cut edges, eliminating the skeleton completely from these sections. Should the parts be particularly small, they may have only small microjoints between them to keep them from tilting up on the table during cutting. Regardless, the parts come off the table grouped for processing.

Nesting itself can also play a role in simplifying the removal of the sheet skeleton and parts, while also speeding up the cutting process. At the most basic level, the grouping of similar or related parts on a section of sheet can help an operator remove and stack those parts together. Taking this a step further, by removing the need for a skeleton between those parts, you save materials and scrapping processes. Image courtesy of Bystronic.

The other value in terms of the quality of the finished product is that, due to the lack of a skeleton, heat can’t as easily migrate across the sheet and affect other pieces because the skeleton’s “web” isn’t there to transfer that heat.

“In the case of thicker materials, heat input is always a concern,” said Arteaga. “That is why, if you are watching a laser cut, you will often see the optic jump back and forth across the sheet during cutting – to allow the heat to dissipate on one side between processes. But because you are essentially cutting the parts away from the skeleton and you are eliminating the webs, there are fewer opportunities for heat interplay. In eliminating the webbing, you eliminate heat pathways.”

Tabs or microjoints can also be a challenge. Speaking to one shop manager who learned by trial and error how best to place microjoints on jobs, Arteaga noted that in some instances the programmer felt he’d optimallly nested the sheet, yet the person in charge of sorting the parts had a great deal of difficulty removing the parts without damaging them.

Automation: A Multifaceted Challenge

As TRUMPF’s Reuther explained, more and more customers are asking about automation and sorting options because of the volume and variety of parts they are trying to manage.

“If you have low volume and a low variety of parts, you might not need an automated process,” Reuther said. “But some companies today may make 10 copies of one part 100 times over the course of a year. This is what we are seeing as a trend in the sheet metal market and the entire industry today. There is a high variety of parts because customers are requesting lower quantities.”

However, as Amada’s Beransky explained, it is difficult to create an automated process that fits the needs of many shops.

“We explain to customers that there is a big difference between a stand-alone machine, automation, and sorting,” Beransky said. “These are each specific steps in the process, and each adds new variables to your process. For instance, when you run a stand-alone machine, you don’t worry about the condition of your slats on the shuttle table as much. But when you automate production, this becomes a concern, because if your cutting conditions are not exactly right, it affects processes later on.

“Another example of what can go wrong is the movement of your shuttle table,” Beransky continued. “If the shuttle table does not move smoothly enough and a part shifts under the skeleton, you will never be able to pick that part up.”

TRUMPF’s PartMaster somewhat bridges the gap between working directly from the pallet and a completely automated process. A conveyor belt delivers processed sheets to an operator who stands in one place to unload and sort the parts. The skeleton is also strategically cut into manageable sections during processing so they can be picked up and easily discarded by the operator.

Beransky explained that shops have to learn a lot when they move toward part sorting capabilities.

“There are three key elements: the condition of your machine, the software used, and the cutting conditions,” he said. “We tell clients upfront what they need to do to maintain their machine and about the software they will have to learn, which is new nesting software created to better manage part separation.”

Amada has a team of about 17 people involved in ensuring that a client’s automated sorting system is going to work properly. There is a solution for most parts, it’s just a matter of whether the financial outlay warrants the result.

“We have to analyze the customers’ parts every time,” said Beransky. “Some parts are very difficult to pick up. They may be too long or too small or too heavy for a particular device. Mostly it is OEMs that are taking advantage of the potential benefits of part sorting technology because they run the same or similar parts often. However, we have installed a couple of systems in job shops.”

Three Levels of Automation

As explained previously, it’s worth considering automation in discrete levels because level can affect the manner in which a sheet is nested and processed.

Say a company invests in a basic load/unload device with a compact storage tower. In this case, if the company wishes to run the laser lights-out, a pallet of finished sheets could be removed with a forklift in the morning and taken elsewhere for processing. As LVD Strippit’s Colle noted, “We are seeing customers taking those pallets off and bringing them to a sorting area where they can very efficiently process the parts. And using a tablet mounted on a stand, as we discussed earlier, they are able to see exactly what nests they are processing and where the parts are required to be stacked.”

In this case, parts may have microjoints attaching them to the skeleton to ensure that no parts are misplaced.

TRUMPF has designed a semi-automated system called the PartMaster that somewhat bridges the gap between working directly from the pallet and a completely automated process. It is essentially a robust conveyor belt that delivers processed sheets to an operator who stands in one place to unload and sort the parts. The skeleton is also strategically cut into manageable sections during processing so they can be picked up and easily discarded by the operator. The ergonomics of this method are better than leaning over a full cut nest and walking around the pallet changer to reach every position, and it has the added benefit of the parts coming to the operator rather than the operator moving to the part – a typical approach in lean manufacturing.

Reuther claimed that this system speeds sorting time for an operator by as much as 30 to 40 per cent.

Bystronic, meanwhile, has its own load/unload system that sorts parts automatically, the Bystronic ByTrans Extended. According to Arteaga, this system works well with long-edged parts that are easy to remove from the sheet skeleton.

Fully automated part picking and sorting is particularly challenging for a number of reasons, as mentioned before – the weight of the part, the size, and the risk of the part dropping below the level of the skeleton and becoming inaccessible. Each machine builder has its own solution to these problems. In Amada’s case, it is custom designs.

For TRUMPF, it is the creation of modular options that that can be custom-fit for the customer. The fully-automated sorting device is called the SortMaster, designed with magnetic grippers and suction cups that can pick up parts of various sizes and stack them on a pallet. The design includes a vibration function that is meant to help dislodge a part from the skeleton if it is somehow dislodged or stuck under the sheet. Even in this design, very small parts may still be ganged together in a piece to be properly removed from sections of the sheet and to save sorting time. Like with any other process, parameters need to be met, and shops need to be properly educated about the functional limitations of the equipment. It can remove parts as large as 1,000 by 1,500 mm and 100 kg using a secondary gripper, and it includes a brush function to clean off the slats after parts and skeleton are removed to ensure the next raw material sheet is placed evenly onto the slats for perfect cutting conditions.

Bystronic, by comparison, has recently partnered with a company called Astes to create a rapid sorting system.

“The biggest challenge with sorting systems, and it is worse now with the advent of fiber technology, is the speed with which the sorting process happens,” said Arteaga. “You can’t afford to have your sorting system being outpaced by your laser. Everyone’s looking for more efficient ways of unloading.”

The Bystronic/Astes cell design has four robotic devices that manipulate the cut sheet. Each device has the ability to switch out its end effectors. These can be changed from large suction cups to small suction cups, or even magnets. The end effectors are changed depending on the size and weight of each piece being removed. These same actuators are used to pick up the fork system that then removes the emptied skeleton, as well as the brushes that clean the slats of the table to remove any slugs. The company has installed this in European customers’ facilities and are in discussions with companies in North America to introduce the system here.

Like any technological investment, part sorting systems need to be right-sized for your environment. It’s also important to ensure that how the job is handled by the nesting programmer creates a finished cut profile that can be managed properly by whomever or whatever is in charge of sorting those parts at the end of the line. As Beransky said, everyone has a lot to learn in the process.

Editor Robert Colman can be reached at rcolman@canadianfabweld.com

Amada Canada Ltd., 905-676-9610, www.amada.ca

Bystronic Inc., 800-247-3332, www.bystronicusa.com

LVD Strippit, 716-542-4511, www.lvdgroup.com

TRUMPF, 905-363-3529, www.us.trumpf.com

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

Aluminum MIG welding wire upgraded with a proprietary and patented surface treatment technology

CWB Group launches full-cycle assessment and training program

Achieving success with mechanized plasma cutting

Hypertherm Associates partners with Rapyuta Robotics

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI